At around eight weeks into her pregnancy, Emily began taking her prescribed folic acid tablet every day. Like many expectant mothers, she knew that folate supplementation helps prevent neural tube defects, but she had never imagined that the form of folate she took might influence the levels of certain “invisible guardians” in her breast milk.

Recently, a study published in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition caught the attention of the nutrition community.

A research team in Vancouver, Canada enrolled 60 pregnant women between gestational weeks 8 and 21, assigning them to two groups: one received the commonly used synthetic folic acid (0.6 mg/day), the other an equimolar dose of (6S)-5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid (5‑MTHF, 0.625 mg/day).

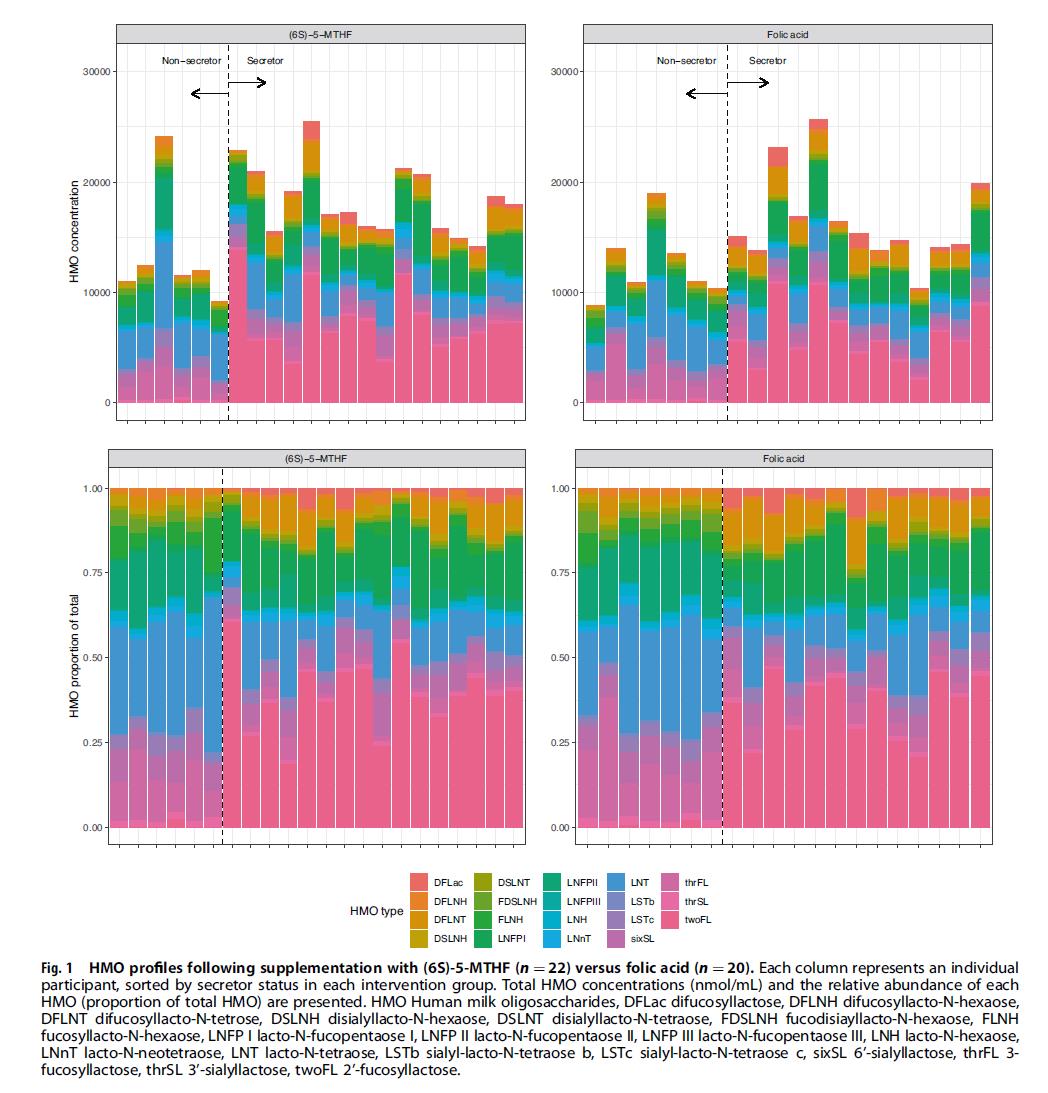

After 16 weeks of supplementation, some participants continued until one week after delivery. At that point, researchers collected their breast milk and analyzed both folate forms and 19 human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs).

HMOs are unique carbohydrates found in breast milk—over 150 varieties exist. Although infants do not directly absorb them, HMOs play essential roles in cultivating a healthy gut microbiome and training the immune system. Among them, 3′‑sialyllactose (3′SL) is particularly notable for helping babies resist inflammation and infection.

While it has been known that HMO composition is influenced by genetics and certain modifiable factors such as maternal nutrition, the specific impact of folate supplementation remained unclear—until now.

An unexpected finding emerged from this study: although total HMO levels did not differ significantly between the two groups, the proportion of Unmetabolized Folic Acid (UMFA) in the breast milk of the folic acid group reached as high as 29%, more than ten times that of the 5‑MTHF group. More notably, data analysis revealed that higher UMFA levels were associated with lower total HMO concentrations and significantly reduced 3′SL.

This suggests that prolonged intake of synthetic folic acid leading to UMFA accumulation could quietly diminish the levels of these beneficial components in breast milk—a signal worth noting for a baby’s long‑term health.

So, is there a way to meet prenatal folate needs while avoiding the potential pitfalls of UMFA?

The 5‑MTHF group in the study points to one answer.

Because (6S)-5‑MTHF is the active reduced form of folate, it requires no metabolic conversion in the body and therefore does not generate UMFA. In breast milk from this group, reduced folate forms accounted for about 98%, with UMFA virtually undetectable.

This form is also known commercially as Magnafolate, a naturalized folate produced without harmful substances such as formaldehyde or p‑toluenesulfonic acid, achieving a safety profile classified as practically non‑toxic. Magnafolate offers expectant mothers and infants a more reassuring approach to folate supplementation.

[Magnafolate® is supplied solely as an active folate raw material and does not directly provide diagnosis or treatment advice to consumers; any supplementation decisions must be made under professional medical guidance.]

References

- Lian Zenglin, Liu Kang, Gu Jinhua, Cheng Yongzhi, et al. Biological characteristics and applications of folate and 5‑methyltetrahydrofolate. China Food Additives, 2022, Issue 2.

- Titaley CR, et al. Human milk oligosaccharide composition following supplementation with folic acid vs (6S)-5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid during pregnancy and mediation by human milk folate forms. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2024; DOI:10.1038/s41430-024-01476-x.

Español

Español Português

Português  русский

русский  Français

Français  日本語

日本語  Deutsch

Deutsch  tiếng Việt

tiếng Việt  Italiano

Italiano  Nederlands

Nederlands  ภาษาไทย

ภาษาไทย  Polski

Polski  한국어

한국어  Svenska

Svenska  magyar

magyar  Malay

Malay  বাংলা ভাষার

বাংলা ভাষার  Dansk

Dansk  Suomi

Suomi  हिन्दी

हिन्दी  Pilipino

Pilipino  Türkçe

Türkçe  Gaeilge

Gaeilge  العربية

العربية  Indonesia

Indonesia  Norsk

Norsk  تمل

تمل  český

český  ελληνικά

ελληνικά  український

український  Javanese

Javanese  فارسی

فارسی  தமிழ்

தமிழ்  తెలుగు

తెలుగు  नेपाली

नेपाली  Burmese

Burmese  български

български  ລາວ

ລາວ  Latine

Latine  Қазақша

Қазақша  Euskal

Euskal  Azərbaycan

Azərbaycan  Slovenský jazyk

Slovenský jazyk  Македонски

Македонски  Lietuvos

Lietuvos  Eesti Keel

Eesti Keel  Română

Română  Slovenski

Slovenski  मराठी

मराठी  Srpski језик

Srpski језик

Online Service

Online Service